You might remember Kalpana—I am happy to report that this year she celebrates her fifth rescue anniversary at Wildlife SOS. Formerly exploited and abused as a ‘begging’ elephant in Uttar Pradesh, Kalpana was rescued in 2019 and brought to the Wildlife SOS Elephant Hospital Campus (EHC) in Mathura for comprehensive...

Bats get an unfairly bad rap, and flying-foxes most of all – a particularly concerning situation considering the mounting threats they are facing. Whether it’s being shot by orchardists (a practice largely phased-out in NSW which we’re still working on in Queensland); getting scared out of their roosts or having them destroyed due to complaining neighbours; or having their extermination advocated for by shock jocks and some of our elected representatives, it’s a seriously tough life.

And this Halloween times are particularly hard as food shortages in recent months have led to a starvation event in South East Queensland and surrounds. It’s a major problem likely caused by a combination of factors including habitat destruction through land clearing, fires, and terrible drought.

The situation doesn’t bode well as a scorching summer looms, and it’s imperative we get ready for perhaps the most direct and distressing impact on flying-foxes in recent years – heat stress events. When the mercury soars (typically above temperatures of 42 degrees, but dependent on other factors such as humidity and with slight variations between species) flying-foxes suffer.

The most shocking example of such a heat stress event occurred in Far North Queensland last November, when more than 20,000 Endangered spectacled flying-foxes suffered horrific deaths. This was the first known mass die-off of the species and an absolutely devastating one with up to a third of the Australian population lost in just days. While that heatwave was hopefully still anomalous enough to be unlikely to occur again this year, the potential for such devastation means we simply have to be ready –the existence of spectacled flying-foxes is at stake.

But regardless of threat status, the welfare impacts on all flying-fox species can be catastrophic in these situations and quick and effective responses are needed across the board. It would be unconscionable to stand by as black or little red flying-foxes suffer just because their populations are in relatively good shape.

Impacts on the welfare of heroic volunteer wildlife carers who get themselves where they’re most needed with little thought for their own wellbeing must also be recognised, and Humane Society International continues to lobby for greater government support for these dedicated and selfless people. If the authorities are going to rely on wildlife carer help in these highly traumatic situations, the very least they can do in turn is be there for them in times of need.

Credit should be given to state government agencies such as the NSW Department of Planning, Industry and Environment and Queensland Department of Environment and Science for the work they have done to communicate with land managers (typically local councils) and turn negative perceptions of flying-foxes around, but so much more is required. The NSW Department is thankfully leading efforts to have best practice guidelines and response strategies developed for heat stress events, and we’ll be at the upcoming National Flying-fox Forum in Canberra helping to turn their groundwork into active policies as a matter of urgency.

While commending the work of the NSW government, it has to be noted that this is the same Department whose Minister is looking to change laws and policy settings that would assist the development of coal mines in NSW, and that they also allow degradation of flying-fox roosts that leaves them less resilient in heat stress events. Flying-foxes may be getting welcome attention, but they’re part of a much bigger system and while the drivers that are threatening them continue not only undeterred but actively supported by our decision makers, we clearly have a long way to go.

With flying-foxes playing such an important pollination role in Australia, there’s a lot at stake. Put simply we need forests, forests need flying-foxes, and flying-foxes need us as tough times approach.

What you can do to assist:

- Help build Humane Society International’s wildlife emergency response fund by donating here. If (when) flying-fox heat stress events occur we’ll make sure your contributions get to the heroic carers in need fast;

- Familiarise yourself with local flying-fox camps so you can help monitor conditions and assist wildlife carers and authorities in an emergency (or even just go and appreciate them!);

- Urge your local council to get ready for summer by putting a flying-fox heat stress strategy in place and ensuring they have the resources and expertise required to respond;

- Consider becoming a wildlife carer yourself – it’s demanding, but extremely rewarding and increasingly needed;

- Share this blog to help raise awareness of flying-foxes and the threats they face!

Evan Quartermain is Head of Programs at Humane Society International and has been with the organisation since 2010. A member of the IUCN World Commission on Protected Areas, Evan is responsible for HSI’s terrestrial habitat and wildlife protection campaigns and programs, with particular focus on legislative reform, flying-foxes, dingoes, and habitat protection through Threatened Ecological Community and Natural Heritage nominations.

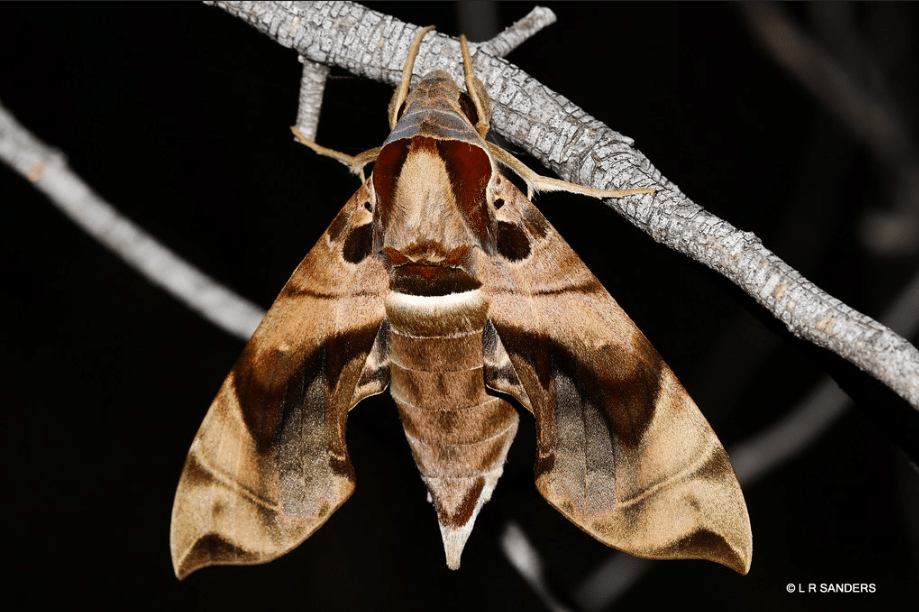

Header Image Credit: Nick Edards