SYDNEY (March 11, 2026)—Humane World for Animals Australia’s marine ecologist, Lawrence Chlebeck is warning against rising calls for a cull of bull sharks, urging Sydneysiders to instead call on their local MPs and relevant ministers to continue investing in technology that will actually keep swimmers safe. As an ecologist, field biologist and environmental consultant, Mr Chlebeck’s work has focused extensively on examining the efficacy of...

When we think of sharks and rays, our minds tend to focus on a few large and iconic animals like great whites, manta rays, and whale sharks. And while these species certainly deserve a central place in our psyche due to their size and magnificence, the biodiversity of this group of animals is truly wondrous and expansive. There is a multitude of lesser known, smaller, and less often seen species that make up the majority of the species that call Australian waters home.

All the weird, wonderful, hidden, and cryptic species of sharks and rays in Australia deserve our concern not only because we share the sea with them, but also because biodiversity is inextricably linked with the health of the oceans. An ecosystem with a greater number of species will be more resilient to changes in the environment than an ecosystem with few species. Australia is recognized as a shark and ray biodiversity hotspot with 322 species – half of which are found nowhere else in the world. Protecting the shark biodiversity of Australian waters is critical to maintain our vibrant seas.

As with all sharks and rays across the world’s oceans, some of our little-known and unique species are also in danger. As part of our Shark Champions campaign with the Australian Marine Conservation Society, we have nominated four under-appreciated species for protection as threatened species under Australia’s federal environment law, the Environment Protection of Biodiversity and Conservation (EPBC) Act; narrow sawfish, grey skate, long-nosed skate and the whitefin swellshark. We are excited to announce that all 4 species have made the final cut for Ministerial Review and on to a list known as the FPAL, or the Finalised Priority Assessment List, which means they will now be assessed as a priority for federal protection.

To save these species it would help if they had a higher profile. So read on and find out more about them:

Narrow Sawfish (Anoxypristis cuspidata)

The Endangered narrow sawfish may look like a shark, but is actually a highly modified ray. Once collected as a trophy, their saw-like snout (for which they are named) is used for locating and immobilising prey. It’s found accross Northern Australia stretching from east coast of Queensland, through the Gulf of Carpentaria, to the coast of Western Australia. Northern Australia is one of the last global strongholds for this species. Historical images and pub decorations document that their range once extended down the east and west coasts of Australia. Sawfishes are among the most endangered of all shark and ray species and are under threat from gill net fisheries. Listing under the EPBC Act could limit the spatial extent of gill netting in Northern Australia and help these populations bounce back.

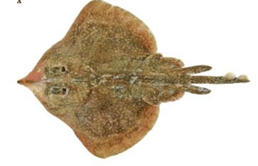

Grey Skate (Dipturus canutus) and Longnose Skate (Dipturus confusus)

Skates are an ancient lineage, deep-dwelling cousins of rays. The Endangered grey skate and Critically Endangered longnose skate are found only in southern Australian waters from New South Wales to Western Australia. Living at depths from 20 down to 700m, they live on a diet of crustaceans. The primary threat to these skates is deepwater trawl fisheries. While skate flesh is sometimes sold as flake, it is more often discarded as bycatch in the indiscriminate trawl nets that scour the ocean floor. EPBC listings would require species specific conservation plans for these imperiled skates.

Whitefin Swellshark (Cephaloscyllium albipinnum)

The Critically Endangered whitefin swellshark is also only found in Australian waters. Swell sharks are named for their ability to greatly expand their belly by swallowing water or air when threatened or caught. Like the skates above, the whitefin swellshark is a common bycatch species in the trawl fisheries of southeastern Australia, and intensive demersal trawling has led to significant declines in the abundance of this species of approximately 75% from 1994 to 2006.

Securing a listing on the FPAL is a significant achievement, but only the first step. We hope the decline in these species is recognised so a conservation plan to rebuild their populations can be developed. These cryptic animals are no less important than the ones whose images we see in our media every day, and it is vitally important that they are not forgotten. With a chance for listing and protection, we can ensure that they are considered and conserved.

A marine ecologist specialising in conservation, research and outreach, Lawrence has spent years working with wildlife, the ocean and the public to engender sustainable relationships between them. He has worked as a field biologist, environmental consultant, naturalist and project coordinator with a BA from the University of San Diego, and an MSc from James Cook University. Lawrence’s work at HSI is currently focused on shark welfare and protection, specifically in regards to culling and control programs, overexploitation, and international protection.

Header Image: Kelvin Aitken